Mexico’s ‘searching mothers,’ alone against the drug cartels and the authorities: ‘We live with more fear than ever’

Five women who are looking for missing family members across Mexico have denounced Claudia Sheinbaum’s failure to address the issue during her presidency. They accuse her of only taking action following the discovery of a mass grave in the town of Teuchitlán. These women also highlight the inaction of the prosecutors’ offices and the threats they’ve received from the cartels

Óscar Antonio López Enamorado wanted to study. But in Honduras, back in 2009, this was an impossible dream. At the age of 19, he left behind a country mired in violence and overtaken by a military coup. He managed to reach the United States. He met some young men who promised him work and a good salary in Mexico. He trusted them. He retraced his steps and crossed the border south. They took him to a ranch in the Mexican state of Jalisco. And there, 15 years ago, in the town of San Sebastián del Oeste, the trail went cold.

His mother, Ana Enamorado, quit the life she had known until then in order to search for her son. In 2013, when she was able to afford the trip to Jalisco, she went to the National Human Rights Commission (CNDH) and asked for help. “A public official from [the NGO] Províctima told me: ‘You can’t go [to that town], it’s very dangerous: not even the police can go in.’ At the Public Prosecutor’s Office, on several occasions, they told me: ‘You can’t go there… nobody can go there. Instead of looking for one person, we’re going to end up looking for two: you and your son.‘”

The ranch in the town of Teuchitlán is just the latest example — the umpteenth — of the incomprehensible scale of forced disappearances in Mexico. Óscar’s story — like that of the 125,000 people who, one day, simply never returned home — is that of many people whose bodies are scattered across a country that has incorporated words like “graves,” “crematoriums,” “extermination centers” and “massacres” into its everyday vocabulary.

Years ago, faced with institutional neglect, this phenomenon of violence was met with a formidable response. This came in the form of women searching for their family members, who became known as madres buscadoras (searching mothers).

María Isabel Cruz, 56, has been searching for her son Reyes Yosimar García since January 2017. He was a police officer in the city of Culiacán and found himself in the middle of one of the turf wars between factions of the Sinaloa Cartel. “After this ranch was [recently] exposed, everyone was horrified… [they’re] unaware that things are the same or worse in other parts of the country.”

In 2018, her group recovered more than 18,000 charred bone fragments, which had been hidden in a well. “No one was horrified, no one said anything. Something extraordinary has to happen for us to [react].” She’s concerned about the “smear campaign” that, she believes, is behind President Claudia Sheinbaum’s recent statements about the searching mothers. “This terrifies us, because the hunt is about to begin. We live with more fear than ever, because we’re more persecuted than ever. What more do we have to go through for the government to recognize the magnitude of these barbaric crimes against humanity?”

The discovery of the mass grave in Teuchitlán triggered the suppressed pain of a country, which has long tried to numb itself to this daily horror. It made headlines around the world and was even brought up by the president at her daily press conference in the National Palace. The mothers processed the news with pain, but they weren’t surprised. It’s not the first time that this has happened, nor will it be the last.

“Every day that passes, we realize that all of this is still going on. What’s coming out now [into public view] was happening a long time ago. We families have been talking about it all this time… and [the authorities] don’t believe us. We already had information from many groups about that place [in Teuchitlán], but they wouldn’t let us [go there],” says Virginia Garay, 53, a member of a group searching for missing people in the state of Nayarit. Her son Brian Eduardo left home one day in 2018 to work at his burger stand. He never returned. She went to Teuchitlán two years ago after receiving an anonymous tip. Garay was warned: “There are still people [operating] there; I can’t guarantee you’ll get out.” She saw trucks coming and going from the site, but there was nothing she could do.

From Jalisco to Tamaulipas

A few days after the discovery of the mass grave in Teuchitlán, the mothers of Tamaulipas came across another site with similar characteristics. Charred bone remains were found. However, this discovery didn’t make as much noise; it didn’t grab headlines.

After Jalisco, Tamaulipas is the state with the second-highest number of missing people in the country. One of them was Rigoberto Mata, the husband of 30-year-old Verónica Guadalupe Francisco, who lived in Monterrey, but disappeared in Nuevo Laredo. “[The prosecutors’ offices] only create a file… and that’s all the help they provide. Last year, as a collective, we got tired of waiting for the Attorney General’s Office to do work. We began to demand that they at least provide us with security, so that we could search [on our own].”

“In Monterrey we repeatedly sought help from the mayor. We planted ourselves outside the [mayoral palace] but didn’t receive any kind of response. There’s been no progress of any kind; it’s discouraging,” Verónica sighs.

The word “disappeared” has barely been mentioned by Sheinbaum since her six-year presidential term began in October of 2024. However, after Teuchitlán exploded into the collective imagination, she announced several legal reforms, which are intended to unify databases of missing people. “The authorities look for ways to stop us… [but] when a group manages to get in and uncover everything, this is what happens. It shows why families don’t believe in the authorities, because we continue to doubt and suspect them,” Garay criticizes.

Sheinbaum argues that the media attention surrounding the ranch, which the mothers and forensic experts describe as an “extermination center,” is a political maneuver meant to tarnish the image of her predecessor, Andrés Manuel López Obrador.

“This government, like all others, tries to say we’re against them, or that we’re trying to [ruin them]. [And their] goal is to make us look like liars. It’s a way of justifying why the [investigative] work was never done,” Garay states. It was the mothers, in fact, who had to raise the alarm in Teuchitlán. The Attorney General’s Office of Jalsico dispatched agents to the ranch in September of 2024. However, for six months, nothing was done to investigate the thousands of pieces of evidence that were scattered around the property: human bone remains, sneakers, clothing, backpacks, toys, ditches in the ground with signs of having served as crematoriums. The Attorney General’s Office of Mexico has been forced to take on the case.

Fear has increased in recent days, following a video allegedly released by the Jalisco Cartel. In the video, it’s claimed that Teuchitlán was not an extermination center, while the mothers and members of the press are threatened. Experts are debating the authenticity of the footage. For Virginia Garay, it’s “the authorities posing as [the cartel], to make us seem like liars.” Whether a real threat or not, all the search parties agree that the pressure of organized crime is a constant risk. Even more so if, as is often the case, they have to go out into the countryside without security or support from the authorities. Unaccompanied, using their own money.

Unidentified ashes

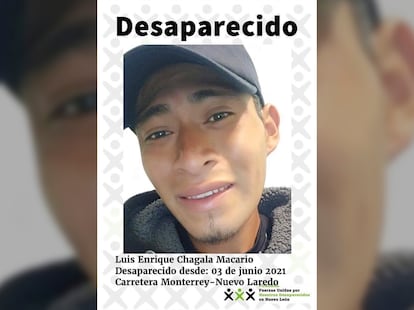

Luis Enrique Chágala, María Antonia Chágala’s brother, disappeared in June 2021 from the city of Nuevo Laredo (although the family hails from Veracruz). Since then, nothing has happened: witnesses have not been interviewed, nor have the owners of the private security company where Luis was working when he vanished. María would like to go to Jalisco to look for any trace of Luis among the abandoned clothes. But she can’t afford the trip. She had to leave her job at a clothing store to pursue her brother’s trail, which is a full-time job.

The searching mothers say that, when they’re not out in the field, they spend their days scouring the internet. Whenever any human remains appear across the country, they attempt to find clues that may lead them closer to their loved ones.

“The government isn’t helping us,” María laments. “The president should show solidarity with the families of the disappeared, because you can’t imagine the pain one goes through, when you spend every day thinking about where they could be. We have to do it alone and risk our lives [in the process].”

“This isn’t just my pain: it’s that of many others. Justice must be done here in Mexico.”

Ana Enamorado, an international figure in the search for the disappeared, hasn’t left Mexico since arriving from Honduras in 2013 to search for Óscar, her son. When the ranch in Teuchitlán was revealed, she shut herself away to cry. “I [usually] go out into the streets to [protest and] take action… but that day, I cried all the time. It was horrible.”

The group she created, the Regional Network of Migrant Families, was one of the organizers of last Saturday’s vigil in Mexico City’s Zócalo, the capital’s main square. Other vigils were held in Guadalajara, Oaxaca and Ciudad Juárez. Hundreds of mismatched shoes were placed in the center of the plazas, like those found at the ranch. This is a new, eloquent way of symbolizing absence.

“I’ve said it clearly: there’s collusion between criminal groups and the authorities,” Ana Enamorado affirms. “[The discovery of the ranch] in Jalisco is a very clear example of this. It’s so obvious that [the authorities] are complicit. It’s not the first time, it’s not the first case.”

Every day, this mother thinks about her son. She wonders about those unidentified ashes that the Jalisco state authorities handed over to her, hoping that she’d accept them. They did the same thing to many other mothers. “It took me seven years to prove they weren’t Oscar’s.”

Translated by Avik Jain Chatlani.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.