The Trump administration’s brief but dramatic suspension of military aid to Ukraine from late February to 11 March exposed critical vulnerabilities in Europe’s defense infrastructure. Though US assistance has now resumed following meetings in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, where Ukraine agreed to a 30-day ceasefire proposal, the three-week pause served as a stark warning about what’s at stake if US support wavers again.

The suspension left nearly $1 billion worth of military equipment in limbo, some already en route to Ukraine or awaiting transit at staging areas in Poland. Despite the White House’s initial statement to AP that there would only be a pause, this temporary halt left the EU as the primary supplier of military equipment to Ukraine—all while Europe was still building up its own military power.

As we analyze what happened during this period, the question remains: Could Europe fill the gap if US aid were to leave permanently?

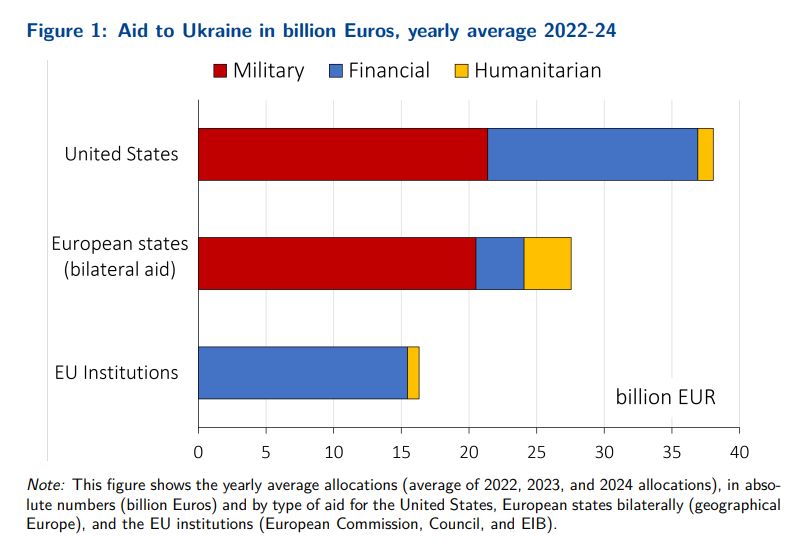

The financial burden

The EU is responsible for over $50 bn in military support to Ukraine. In comparison, the US has supplied over $65 bn since the Russian invasion in February 2022. The US’s pause in assistance would mean that the EU would have to more than double its current spending in the long term.

With the EU’s fragmented nature and significantly weaker industrial base, this presents more than just a budgetary challenge. To compensate, Europe may have to look beyond its borders to fulfill the needs of Ukraine’s military.

The surprising strength hiding in plain sight

As of now, the US has been the largest supplier of Infantry Fighting Vehicles (IFVs), Howitzers, Multiple Launch Rocket Systems (MLRS), and Armored Personnel Carriers (APCs), according to the Kiel Institute.

However, a broader analysis of NATO’s capabilities reveals that the US may not be as indispensable on the ground as once thought.

According to the International Institute for Strategic Studies’ The Military Balance 2024, non-US NATO countries, many of which have supported Ukraine’s efforts, hold a significantly larger inventory of military ground equipment than the US. This inventory includes tanks, APCs, IFVs, and artillery, with inventories of IFVs and self-propelled artillery outnumbering US stocks by a ratio of 2.2:1 and 3.5:1, respectively.

The catch? Much of this equipment is reserved for NATO defensive strategies and cannot be easily allocated to Ukraine without sufficient replacement.

The sustainability puzzle everyone’s trying to solve

Replacing these diminishing stocks has become a priority for many of Ukraine’s supporters.

In March 2024, the EU allocated 500 million euros to the Act in Support of Ammunition Production, implemented to increase ammunition production for the EU and Ukraine. Additionally, the EU has proposed an €800 billion defense plan to improve its military capabilities.

While these actions show the EU is committed to enhancing defense and self-sufficiency, the timeline for implementation and impact on production capacity remain uncertain. This uncertainty stems from multiple other hurdles besides spending that the EU defense industry must overcome to provide sufficient support to Ukraine.

Systemic issues within EU Defense

These hurdles stem from the historically weak governance displayed by the EU, in which member states lack the political mechanisms to effectively embark on joint ventures within the defense industry. This weakness leads to fragmentation, with companies primarily focusing on the needs of their home country.

The result? Multiple companies making small quantities of similar products. Consolidating these companies could increase their manufacturing capabilities and prevent the logistical nightmare that Ukraine now faces with a wide array of different systems serving the same purpose.

Secondly, the EU relies heavily on battle-tested US systems. While these systems enhance their defense, dependence on external suppliers undermines domestic manufacturing capabilities and innovation.

The fine print that could stop your weapons from reaching Ukraine

These systemic challenges are exacerbated by regulatory obstacles, particularly those stemming from US control over certain weapon systems and technologies. The International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR) create additional barriers for the EU when providing military aid to Ukraine.

Take the F-16, relied upon by EU countries but transferable to Ukraine only with explicit US permission. This applies to any equipment with US components—such as the Swedish Gripen jet with its General Electric engine.

These regulations underscore the EU’s limited ability to meet Ukraine’s defense needs without external approval independently.

Why your air defense system isn’t as good as America’s

The possibility that ITAR can significantly impact the EU’s ability to provide aid to Ukraine highlights a major weakness in Europe’s defensive strategy. The lack of manufacturing and innovation within the EU has given US weapon systems the advantage.

This advantage is evident when comparing the Patriot with the joint French and Italian SAMP/T. While the SAMP/T has some advantages compared to the Patriot, such as further intercept range, lower manufacturing cost, and ability to track more threats, the downsides become apparent when looking deeper.

The SAMP/T is designed primarily to deal with aircraft and ballistic missile threats. It lacks the ability to target drones and cruise missiles, which have proven to be serious issues for Ukraine. Additionally, availability matters: currently, there are 30 Patriots in the EU, while only 15 active SAMP/T systems exist.

This means that from the same 6% inventory loss, the EU can provide two Patriots for every SAMP/T. While it is difficult to get an exact idea of how long it would take to produce more SAMP/T systems, Raytheon’s president of land and air defense systems told Politico that,”It takes us 12 months to build a Patriot radar, but it takes us 24 months to get all the parts.”

Since Patriot manufacturing infrastructure is much more robust and larger than SAMP/T, it could take decades to produce enough of these systems to significantly impact European skies.

The rockets that changed the war could disappear

Air defense is not the only area where the gap between EU and US technology is evident. As shown on Ukraine’s frontlines, artillery, especially long-range strike-capable MLRS equipment, has played a key role in Ukrainian successes, such as the liberation of Kherson in 2022.

Currently, the primary MLRS in Ukraine’s (and even the EU’s) arsenal capable of such long-range strikes is the US-made HIMARS and M270. Their ability to use guided munitions sets these systems apart from others.

The GMLRS rocket is NATO’s primary guided rocket munition, allowing the HIMARS to fire up to 6 rockets with conventional and cluster warheads at a range of 70 km.

These guided rockets have had devastating effects on Russian logistics, command centers, and air bases. However, Ukraine has become less reliant on these systems for deep strikes as the battlefield evolves, increasingly using drones for such missions.

Although Ukrainian commanders have claimed that 70-80% of these strikes are successful, the downsides are not to be ignored. Drones used in these strikes typically cannot penetrate hardened shelters and bunkers. Moreover, while a drone’s slower speed may help hide from radars, this also allows the target location sufficient time to prepare for a strike and evacuate important assets.

The eyes in the sky you didn’t know you needed

For GMLRS and drones to be used to their fullest extent, targets must first be identified. While Ukraine can conduct intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) with aerial systems and ground incursions, the most effective way of acquiring targets is with ISR satellite networks – where the US has a near-monopoly.

The US is currently known to operate 247 military satellites, with the closest runner-up in the EU being France, with just 17 known satellites. Losing access to this intelligence network has been detrimental to Ukraine, leaving them not only with an inaccurate picture of the battlefield but also without the advanced warning of missile launches that these satellites provided.

Help on the homefront

The importance of domestic manufacturing has not been lost on Ukraine. Ukraine has prioritized defense spending, with a projected $50 billion defense budget in 2025 and continued efforts to expand weapons production.

Since 2022, Ukraine has increased ammunition production by nearly 25 times, producing 2.5 million shells of indirect fire munitions in 2024. More impressively, Ukraine has exceeded its goal of producing 10,000 medium-range drones, 1,000 long-range drones, and 1 million FPV drones.

This production infrastructure includes domestic and foreign companies, bringing Ukraine to just under 650 defense contractors operating within its borders. This homefront industry lends credence to PM Shmyhal’s statement: “Our military and the government have the capabilities, the tools, let’s say, to maintain the situation on the frontline.

Despite the increase in production, Ukraine’s domestic manufacturing will not be able to supplement the loss of advanced technologies provided by the US for decades to come. Thankfully, Ukraine is not a stranger to pioneering new and sometimes unconventional ways of defending itself.

We’ve seen this with the Sea Baby, which to this day leaves the Russian Black Sea fleet sitting in fear at its port, and the wide-scale use of FPV drones to destroy ground threats. Ukraine’s competence with drone technologies and tactics will become a crutch that it must stand on more in the absence of US aid. According to Mykola Bielieskov at “Come Back Alive,” FPV drones now make up 70% of the strikes against enemy troops within the 20km–30km range.

The countdown you should be watching

Despite the challenges presented by the halting of US military aid, Ukraine and its supporters have demonstrated a willingness to enhance their capabilities in their attempts to bridge the gap left by the US. These efforts will require substantial financial, industrial, and logistical investment, putting the collective political will of all involved to the test to ensure sufficient support reaches Ukraine.

In the short term, however, it is apparent that the EU cannot fully make up for the loss of US assets and intelligence on the battlefield. While Europe may be able to provide more armor and ground equipment, this isn’t Ukraine’s most pressing need.

According to Bielieskov, “Ukraine has 3-6 months of supplies thanks to Biden’s final aid packages, but after that, the pain points will be air/missile defense rather than frontline combat.” This 3-6 months is far from the years, if not decades, the EU will need to build up its industry enough to provide Ukraine with what it needs to defend itself.

However, war is unpredictable and does not always favor the stronger belligerent. From the banks of the Delaware River to the mountains of Afghanistan, resilient people have made do in their fight against inconceivable odds, and the people of Ukraine have so far shown the world that they are resilient indeed.