From roughly 2013 to 2021, Chinese diplomats often adopted an aggressive approach that became known as “wolf warrior” diplomacy. The term was derived from the name of a popular nationalist Chinese action film, and in practice, wolf warrior diplomacy took the form of Chinese officials publicly using tough and often threatening language toward other nations. Over time, this approach resulted in negative ramifications for China’s bilateral relationships, and Beijing has since shifted to a more careful and respectful public messaging strategy.

Since US President Donald Trump’s election this past November, Washington sometimes appears to be borrowing a page from the “wolf warrior” playbook, using harsh public rhetoric as a pressure tactic. In late December, Trump shared a Truth Social post that read, “Merry Christmas to all, including to the wonderful soldiers of China, who are lovingly, but illegally, operating the Panama Canal.” Over the next two months, Trump declined to rule out a military takeover of Panama’s sovereign territory, threatened tariffs on Colombia, instituted tariffs on Mexico, and issued a harsh message to the region: “We don’t need” Latin America.

With the United States now engaging in a wolf warrior–like discursive strategy of its own, particularly in its treatment of Washington’s Latin American allies and partners, Beijing seems to be using this opportunity to flip the script. China is deceptively promoting itself as an alternative, more altruistic, partner to the region.

Beijing’s shift

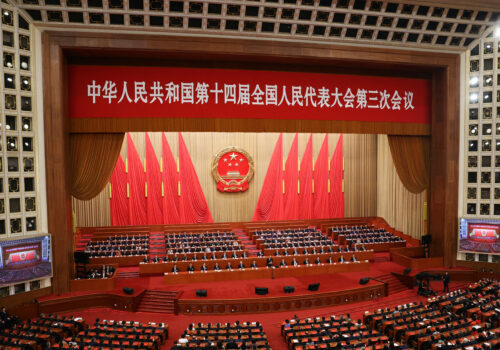

During a press conference held on the sidelines of the recent “two sessions,” the annual meeting of China’s rubber stamp legislative bodies, a Brazilian reporter asked Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi how China will counter US efforts to distance Latin American and Caribbean (LAC) countries from China. Wang’s response was a staunch defense of the region’s agency and autonomy. “What people in LAC countries want is to build their own home, not to become someone’s backyard; what they aspire to is independence and self-decision, not the Monroe Doctrine.” China’s foreign ministry translated this statement into Spanish and amplified not just on its website, but on multiple Chinese diplomatic X accounts.

The foreign ministry’s tone at this year’s two sessions was notably subdued compared to previous years, when Wang and his bellicose predecessor Qin Gang aggressively attacked the United States and its allies and openly celebrated Beijing’s relationships with like-minded authoritarians around the world. It’s difficult to imagine now, but there was a time when Beijing’s public messaging sounded significantly more antagonistic and combative than it does today.

During the era of wolf warrior diplomacy, the Chinese foreign ministry routinely responded to questions from foreign journalists with open hostility. One diplomat publicly called his counterpart a “delinquent nobody.” Another compared small countries who criticized China to lightweight boxers picking on a heavyweight. It was not uncommon for Chinese representatives to storm out of international meetings or shout at their foreign counterparts. To observers of the Chinese Communist Party’s internal shuffling, it appeared this confrontational behavior was, for a time, rewarded by the party’s central leadership. More recently, however, there’s been a shift, and Beijing has transferred many wolf warriors to low-profile departments or retired them.

Wolf in sheep’s clothing

Core to China’s recent charm offensive in Latin America is a narrative of mutual respect for the sovereignty and independence of countries that, Beijing claims, share China’s historical experience with imperialism, poverty, and helplessness against the whims of developed Western countries. This is why Beijing’s foreign ministry spared no time in responding to Trump’s Christmas wishes with an affirmation of China’s supposed respect for Panama’s sovereignty over the Canal. Since then, the foreign ministry has issued six more statements on Beijing’s respect for Panama’s non-negotiable sovereignty and independence, and China’s firm opposition to “abuse or coercion” of Panama. Even the news of Panama’s February announcement that it would not renew its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) agreement was met with a lengthy response from a foreign ministry spokesperson encouraging Panama to resist external influence and extolling the virtues of the BRI as a public good built on a spirit of “peace and cooperation, openness and inclusiveness, mutual learning and mutual benefit.”

While officials in Beijing made a show of contrasting the United States’ aggressive tone with China’s supposed altruism, Chinese diplomats based in the region doubled down on this effort. Earlier this month, the Chinese ambassador to Panama published an article in La Estrella de Panamá titled, “US, please learn some respect.” Meanwhile, the X account for the Chinese embassy in Panama has consistently posted about China’s supposed support for “the Panamanian people in their just struggle to recover and defend the sovereignty of the Canal” since late December.

This strategy has not been contained to Panama. Amid a heated dispute between Trump and Colombian President Gustavo Petro over the mistreatment of deportees, Beijing’s ambassador to Colombia told the local newspaper El Tiempo that China-Colombia relations were at an all-time high since the countries established diplomatic relations forty-five years ago. During Wang’s speech at last month’s Munich Security Conference, the ambassador also posted on X that “it is not China that is really challenging the [international] order, breaking commitments, and withdrawing from international organizations.”

Meanwhile, in response to Trump’s threats to impose tariffs on Mexico, a foreign ministry spokesperson told reporters, “it is China’s consistent position to oppose hegemonic, domineering, and bullying practices in international relations,” and Li Xing, a professor at the Guangdong Institute for International Strategies told Reuters that Trump’s tough approach to tariffs would benefit China, as it would incentivize countries to hedge their bets against Washington.

Despite couching China’s current diplomatic approach in humanistic rhetoric, Beijing’s Latin America playbook remains as coercive and underhanded as ever. Chinese diplomats convey messages of peace, cooperation, and respect while Beijing props up dictators, exports surveillance technology, throws the weight of its economy behind efforts to strong-arm smaller countries, and tacitly supports criminal networks undermining the region’s safety and security.

While Beijing’s foreign policy playbook has remained consistently belligerent, China’s public messaging strategy toggles between aggression and courtesy to suit the environment in which Beijing is operating. Now, China is maximizing its gains by adopting a deferential and polite tone that seeks to make the United States look like an imperialist aggressor by comparison—and the US government is playing into Beijing’s hands.

Regional leaders’ responses should be a warning to the US

In January, US Secretary of State Marco Rubio dismissed the risk of pushing Latin America toward Beijing as “absurd,” citing the administration’s recent successes on trade, migration, and Panama’s BRI membership. However, as several observers have argued, the Trump administration needs to evaluate the long-term implications of this approach with a view towards minimizing space for China to build wedges between the United States and its allies.

Some regional leaders are already assessing their country’s level of risk due to economic dependence on the United States and considering the benefits of diversifying their partnerships. Recently, a group of South American officials, diplomats, and trade experts told Reuters that China’s trade lead dulled the impact of Trump administration trade measures. This includes one senior Brazilian diplomat who said that “Trump’s trade tariff threats—coming after years of ‘neglect’ from the United States—would push countries to look for less risky alternatives like China.”

It doesn’t have to be this way. The United States has the option to leverage an important competitive advantage: its values. Many Latin American countries are facing grave security and human rights challenges, and the solutions that local human rights defenders say they need—an independent civil society, a free press, and judicial independence—are in direct opposition to China’s system. Beijing is loudly signaling respect for the region, but this respect has limits. While China is sure to stay silent on the importance of democratic norms for the prosperity of the region, Washington can and should embrace the achievements of US-backed organizations that have successfully reinforced the work of local rights defenders in recent decades. Accordingly, the United States should employ a humanistic messaging strategy, one that draws attention to Beijing’s hypocrisy and treats US allies and partners with the respect they deserve.

Caroline Costello is a program assistant in the Global China Hub at the Atlantic Council.

Further reading

Fri, Mar 14, 2025

Five takeaways from Beijing’s largest annual political meetings

New Atlanticist By Melanie Hart

Chinese leaders signaled that they will stick to their state-managed economic approach and view Washington as their greatest external threat.

Wed, Mar 12, 2025

China’s economic plans prioritize consumption—but only on paper

Sinographs By Jeremy Mark

At last week's meeting of the National People's Congress, China declared consumption as the number one priority. But will the spending plans actually support consumers and businesses?

Mon, Jan 27, 2025

Expert context: What’s going on with Trump and the Panama Canal?

New Atlanticist By

With US President Donald Trump focusing on the critical waterway early in his second term, Atlantic Council experts explain how the canal came about, why it matters today, and what to expect next.

Image: The flags of Panama and China are seen during a meeting held with Chinese and Panamanian companies to sign several trade agreements, in Panama City, Panama August 26, 2024. REUTERS/Enea Lebrun.