On April 12, the Navy held a symbolic keel-laying ceremony for the U.S.S. Constellation—the lead ship of a new class that will bring frigate-class warships back to the U.S. Navy after the service’s last operational frigate, the USS Simpson, was decommissioned in 2015. While construction of Constellation’s components began much earlier, a welder etched the name of the ship’s sponsor in a plate that will be fixed to its hull.

The Constellation’s name echoes that of another lead ship—one of six frigates procured by the fledgling U.S. government in the 1794 Naval Act to respond to piracy in the Mediterranean. These were the U.S. Navy’s first ships.

Much like Constellation’s illustrious forbearers, the Navy intended for the new frigates to enter service rapidly and affordably amidst growing international tensions. This time, there would be no reinventing the wheel—developing a risky, unproven avant-garde design from scratch. Instead, the Navy took the hull of a popular Italian-designed frigate and plugged in a bunch of proven American weapons and systems. That seemed like a surefire formula to ramp up warship production, should a conflict erupt with China in the Pacific Ocean.

But despite Constellation’s keel-laying ceremony, the preceding four months have substantially depressed prospects of the class’s rapid entry into Navy service. First, in January of 2024, the Navy admitted that the frigates would arrive a year behind schedule due to a shortage of skilled workers. Then, in March, the delay grew to 15 months. Finally, on April 2, a devastating accounting of naval construction programs revealed the new frigates were three years behind schedule. Even the keel-laying ceremony came eight months later than originally projected.

What went wrong?

Why the U.S. Navy Wants to Bring the Frigate Back

In 21st century navies, surface warships (or ‘surface combatants’ in Navy parlance) run on a size spectrum from small patrol or fast attack boats and corvettes to medium-sized frigates, big destroyers, and (very rarely today) cruisers. Some designs are specialized for anti-submarine, anti-aircraft, and mine warfare—others are general purpose ‘multi-mission’ ships.

At present, the Navy has a strong force of large surface combatants—notably the Arleigh Burke-class destroyer—but virtually no small surface combatants suitable for high intensity warfare. But it wasn’t always this way.

During the Cold War, the Navy operated versatile Oliver Hazard Perry-class missile frigates (also known as FFG-7s) armed with Harpoon missiles for battling ships, SM-1 medium-range missiles to shoot down aircraft and incoming missiles, torpedoes and onboard SH-2 or SH-60 helicopters to battle submarines, and both 3” gun turrets and 20-millimeter Phalanx cannons to blast closer air or surface targets. Three shipyards churned out eight FFG-7s per year—51 entered U.S. Navy service, four were sold to Australia, and 16 more were built in Australia, Spain, and Taiwan.

But post-Cold War (between 1994-2015), the Navy decommissioned or donated all of its frigates which, admittedly, were difficult to modernize. They were replaced with smaller, ostensibly cost-efficient corvette-sized warships called Littoral Combat Ships—designed to plug-in modular, mission-specific equipment packages. But the LCSs program was a disaster, resulting in expensive ships too lightly armed to handle China’s rapidly improving Navy.

The Navy cut LCS production early, and even began decommissioning relatively recently built LCSs. (though, at least 15 will remain in a mine warfare role). As the service’s powerful but old Ticonderoga-class cruisers age out of service, that leaves the Navy’s big destroyers shouldering nearly all of the surface warfare missions.

With China’s growing Navy on the mind, Navy planners wanted to bring the frigate back. To avoid risking delays and spiraling costs when developing all-new technologies—risks which doomed both the LCS program and the concurrent Zumwalt-class stealth destroyer, and hampered the Ford-class carrier—the Navy adopted a conservative approach to its future FFG-X frigate by selecting an already mature design and plugging in advanced weapons and sensors already developed for its destroyers. That seemed sure to minimize R&D costs and delays, making it possible to rapidly churn out viable fighting ships in short order.

In April of 2020, the winner of the competition was revealed to be Italian shipbuilder Fincantieri’s FREMM multi-mission frigate. 20 FREMMs of varying configuration (anti-air, anti-submarine, and general purpose) have been commissioned since 2012, serving the navies of Egypt, France, Italy, and Morocco.

Fincantieri’s Wisconsin-based Marinette Marine shipyard was contracted to build the first ten ships (at rate of 3 vessels every two years) for $1.2 billion per vessel—save for the lead USS Constellation, priced at $1.386 billion. Thereafter, the Navy had the right to allow other shipyards to simultaneously builds Constellation-class ships, too.

Overall, the Navy’s 30-year-plan envisioned building up a force of 58 frigates, with at least 20 being in the initial ‘Flight 1’ configuration and the remainder being a future, improved Flight 2 model. The first twelve will all be based at Everett, Washington for operations in the Pacific Ocean.

Each frigate has the means to undertake missions by itself in lower threat environments—sparing the use of more expensive destroyers—or can fight in high-threat scenarios when cooperating with other friendly warships. They are particularly appealing as escorts.

Why Such a Big Delay for USS Constellation?

Two over-laying issues appear responsible for the three-year delay—one specific to the ship, the other affecting the U.S. Navy across the board.

Starting with the latter, the United States broadly lacks adequate workforce and production capacity in its shipyards to support Congress’s ambitions to grow the fleet—particularly in the wake of the Covid pandemic. A shortage of skilled workers (white and blue collar alike) at Marinette shipyards has even compelled the Navy to grant $50 million dollars to the company for bonuses to incentivize employees to stay. Understaffing delays are compounded by lingering Covid-era supply-chain problems.

Thus, the 3-year delay to the Constellation is matched by 2 and 3 year delays for Virginia-class attack submarines, over a year’s delay for the aircraft carrier USS Enterprise, and 12-16 month’s delay for the first Columbia-class ballistic missile submarine. Thus, these problems can fairly be seen as systemic, rather than an issue with the Constellation’s development in particular. Admittedly, the Navy also blamed completion of Marinette’s work—building LCSs and their up-gunned Saudi MMSC variants—for slowing progress on the Constellation-class.

But the other part of the delay seems to be that the contracted design agency Gibbs & Cox substantially enlarged the ship to meet Navy requirements—specifically, more stringent standards for handling in heavy seas and survivability than those of European navies.

But while lengthening ships can be done at reasonable cost—and FFG-62 is indeed 23.6 feet longer—it’s also four feet wider at the waterline. Widening a ship’s ‘beam’ tends to force alterations across the entire vessel—and indeed,“almost every drawing of the FREMM” was altered, according to USNI. Lengthening and widening also upped the ship’s displacement from 6,890 to 7,490 tons at full load.

While Navy officials insisted back in 2021 that these changes wouldn’t cause major alterations or delays, new reports indicate that the FFG-62 design will have merely 15% of parts in common with other FREMM frigates, not the 85% originally promised.

And the changes to the original design are so extensive that Vice Admiral James Downey told media (in April of 2024) that the ship’s design was only nearing 80% complete, preventing advanced planning of construction at other shipyards. (Oddly, a program chief had claimed the design was 80% complete in August of 2022 as well.)

The Navy has thus miscalculated its ability to deliver an only lightly modified ‘Americanized’ FREMM frigate. Perhaps the Navy ought to have committed to a (literally) leaner design, even if that meant revising certain standards. But from another point of view, perhaps complex revisions were inevitable, due to the intense combat scenarios the Navy expects these ships to handle.

There is concern that Constellation-class frigates displace roughly three-quarters the mass of a U.S. destroyer, but have only one-third as many missiles cells—32 compared to 96. After all, once a ship exhausts those cells (most likely batting away enemy attacks) it becomes vulnerable, and likely is compelled to return to port to reload as the ability to replenish at sea is limited.

Some argue that there appears to be spare space on the bow to increase missile cells to 48—an option that a report by Congressional Research Services (CRS) estimates to cost only $16-24 million (in 2019 dollars), a 1.3-2.2% increase in cost. That seems like a no brainer for a 50% increase in fighting endurance, but it’s possible that estimate doesn’t account for the need to displace whatever lay under the deck and delays redesigning the ship in general. The Navy may also have intended to reserve that space to install future capabilities it’s been eyeing for the frigate, including a 150-kilowatt laser to sustainably blast approaching drones or missiles, or the more potent SLQ-32(V)7 electronic warfare system.

Other challenges loom in the Constellation-class’s future, including the continually differed matter of identifying which additional shipyard(s) may be tapped to supplement frigate construction—a necessary step to ensure the Navy can rapidly build up its frigate force at the originally promised rate of 4 frigates per year. However, the Pentagon insists it can’t move on that until the Constellation completes system integration and testing.

There is also the matter of likely cost-growth, with CRS forecasting a 17%- 56% cost increase per Constellation-class frigate after the initial 10 ships.

A Tour Onboard the Future USS Constellation

Constellation-class frigates will combine four Rolls Royce diesel-electric motors with two General Electric gas turbines—a configuration known as CODLAG. The diesels suffice for fuel-efficient cruising, while the turbines kick in at high speeds of 35 miles per hour or greater. The engines will turn two fixed-pitch propellers, designed to minimize noise so ship’s crew can better listen for submarine threats. A crew of 145 personnel may suffice to operate the vessel, with accommodations for up to 200 personnel.

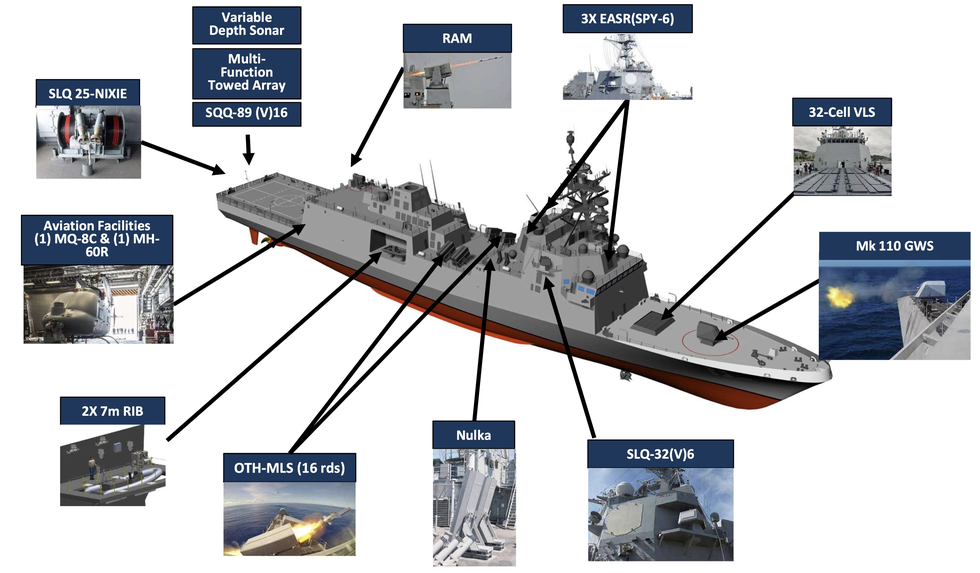

Unlike some European FREMM frigates, the Constellation-class (or FFG-62) will be a multi-mission design—virtually a ‘mini-destroyer’ armed for anti-submarine, anti-aircraft, anti-ship, and even electronic warfare. It will use a streamlined variant of the Aegis Combat system Baseline 10 called Combat SS-21, and will be able to network its weapons and sensors with other ships and aircraft via Common Engagement Capability technology.

For submarine-hunting, the FFG-62 will employ both a CAPTAS-4 variable-depth sonar (preferable to a bow-mounted sonar) and a TB-37 towed sonar array mounted on the stern, along with an onboard MH-60R Seahawk helicopter to help detect submarines. Though the frigate lacks anti-submarine torpedo launchers (despite an option to install Mark 32 SVTT launchers), its Seahawk helicopter does have anti-submarine torpedoes. In the future, the Navy might also deploy anti-submarine missiles compatible with its vertical launch system.

For battling other surface ships, the Constellation class has 16 deck-mounted launch canisters for radar-guided Naval Strike Missiles with a max range of 120 miles.

A software-re-definable AN/SPS-73(V)18 NGSSR radar helps detect surface ships as well as aiding with navigation, as does the frigate’s onboard MQ-8C Fire Scout drone helicopter equipped with an Osprey-30 AN/ZPY-8 spherical search radar, a laser designator, and EO/IR cameras. The Fire Scout fits beside the Seahawk in the aviation hangar. Two 7-meter-long Rigid-hull Inflatable Boats are also tucked into the frigate’s sides.

The ship’s first line of defense against enemy aircraft and missiles will come from 32 Mark 41 vertical launch cells nested inside its front hull. These cells were initially designed for the RIM-162 Evolved Sea Sparrow medium range missile (which can be quad packed four per cell) and the SM-2 long-range missile.

However, Congress required the Navy install larger ‘strike’ cells that could accommodate long-range Tomahawk land-attack missles, anti-ship cruise missiles, and the ultra-fast SM-6 missile, which can be used both for ballistic missile defense and as a surface-attack weapon.

As important as the missiles is the primary sensor—an AN/SPY-6(V)3 radar using jam-resistant AESA technology. Unlike the rotating carrier-based EASR radar it’s derived from, the (V)3 has three fixed arrays on different facings of the ship’s superstructure capable of large area ‘volume search’ and targeting alike. That said, Constellation’s radar will inevitably have less range and sensitivity than refurbished or brand-new Burke destroyers, which will count 96 sr 148 radar modular arrays (RMA) between their four radars, compared 27s RMAS between three radars on FFG-62.

For threats that get within close range of the frigate, it has several last-ditch defenses. These include a Mk110 Mark 3 autocannon turret on the bow that can spit 3.5 programmable air-bursting 57-millimeter shells per second out to range of 5.5 miles, and a SeaRAM launcher atop a rotating pedestal on the aviation hangar loaded with 21 RIM-116 Rolling Air Frame missiles effective out to 5.6 miles. The vessel can also launch Nulka decoys (to lure enemy missiles off course) and Nixie towed decoys (to hoodwink torpedoes).

The frigates will also be adept at electronic warfare offense and defense, thanks to its SLQ-32(V)6 (Slick-32) electronic warfare system. This subvariant is capable of detecting, classifying, geolocating, and jamming enemy signals, including those used to guide anti-ship missiles and kamikaze drones.

So, in theory, the Constellation-class should be well-rounded enough to face diverse threats—though, with an asterisk regarding missile capacity. However, the smooth integration of its components is not guaranteed, as is already made apparent by the time-consuming design alterations required to accommodate U.S. equipment and meet Navy standards. Time will tell if the Navy and its contractors can find ways to make back some of the 36 months they are behind schedule.

Sébastien Roblin has written on the technical, historical, and political aspects of international security and conflict for publications including 19FortyFive, The National Interest, MSNBC, Forbes.com, Inside Unmanned Systems and War is Boring. He holds a Master’s degree from Georgetown University and served with the Peace Corps in China. You can follow his articles on Twitter.